Book Review: “Settlers: The Myth of the White Proletariat”

In his 1983 book, Settlers: The Myth of the White Proletariat, J. Sakai provides excellent insight into the nature of racism, the White left, and the position of Black and other oppressed people in the U.S. To help us understand these domains, Sakai breaks down settler colonialism more broadly, including the U.S. as a settler-colonial state, White people as settlers, and the rest of us as people of oppressed nationalities within this settler-colonial state. The roots of this system lie in Europe’s parasitic and patriarchal ruling class, which, in its stunted mental state, disrupted societies’ inclination to consider the needs of the broad community, including the environment, and consistently placed its desire for power over others over societies’ long-term health and perpetuation.

A particular expression of this greed was the enclosure movement that lasted in England from the 14th to the 19th centuries. 2 In this movement, the establishing European capital class asserted control over the land and, beginning in the late 18th century, the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, forced untold thousands of English people off the land into factories where they would be forced to work for a wage and purchase their means to live from this same ruling class. The enclosure movement contributed to creating a class of people who, rather than struggling in England for a fairer outcome, sought their great estates in the Americas instead. That this would come at the expense of Afrikan and Indigenous people, and, eventually, work its way back to them, was not a significant enough concern to stop the wave of settler invasion. This is one of Sakai’s core contentions: The character of the settler, rooted in a pursuit of land, material advancement, and class upward mobility, makes it a parasitic class. Any group of people that relies on them for solidarity will be gravely disappointed.

As the industrial revolution continued and labor unions developed, the struggle of the settler working class against the settler capital class unfolded. Sakai takes us to places like Detroit’s auto industry and Pittsburgh’s steel industry and argues that what we are seeing is a conflict between sub-classes of the settler class over the booty of the settler colony. So, to see a multi-racial working class that needs to work through its differences is a fundamental error. Rather, there is a European settler nation at war with the Afrikan, Indigenous, and Asian nations and constantly working to subdue them and build the settler colony. There are classes within these nations, yes, but the primary conflict or contradiction is a national one.

Sakai is building on an analysis developed by communists, including Friedrich Engels and later Vladimir Lenin, who described Tsarist Russia before its defeat by the Socialist Parties in 1917 as a “prison of nations.” In this framework, there is an oppressive nation, in this case, the Russians, holding other oppressed nations or nationalities within its borders. Applied to the U.S., Europeans become the oppressing nation, and Afrikans, Indigenous peoples, Asians, and Latin American peoples become the people of oppressed nationalities. Sakai begins the book detailing the genocide required to execute the initial theft of land, labor, and destinies of the people Indigenous to the Americas, the bringing of premature death to 40M to 50M people. This story is then carried across the centuries as it pertains to us, he would call New Afrikan people, Puerto Ricans, Filipinos, Japanese, Chicanos, Chinese, and even the Irish in relation to England. Sakai rather subtly makes the case that it is not the ending of racism that New Afrikan people need, but national liberation. In this project, we will not be able to look to the White settler left as a model, or for much support, but will need to look to anti-colonial struggles across the world.

Lest we think Sakai believes this is a simple case of good New Afrikan people versus bad European settlers, Sakai devotes considerable effort to drawing our attention to the issue of neocolonialism. Under neocolonialism, a class develops within the colonized people, and it is they who, for a relatively cheap price, carry out the strategies of the White ruling settler class. Sakai very persuasively takes on Black men, often framed as luminaries in the civil rights tradition, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Booker T. Washington. Were this book written today, he might’ve added U.S. Democratic Minority Leader, and Zionist apologist, Hakeem Jeffries, and National Action Network Director, Al Sharpton, who has called for U.S. military involvement in Haiti despite the catastrophic history of both U.N. and U.S. involvement.

There was one part of history that seemed to go unaddressed in Sakai’s critique of the White left, and that was the success of the Communist Party and the involvement of a number of New Afrikans like Harry Haywood and Claudia Jones in the 1930s and 1940s. I also thought it would benefit from more attention to how the internal crises of capitalism lead to settler colonialism and imperialism, which could help us understand how attacks on countries like Iran are simply a matter of time, under capitalism, its constant need to expand requires it. But these are minor bones to pick. Settlers is a great and paradigm-shifting read.

I read this book with a study group of those of us with White settler mothers. Shouts to everyone who participated in that effort, it helped me to understand that text and its value. Who says we shouldn’t talk about politics in our families?

This review is published with the permission of Daughter's Magazine where it appears in the fall 2025 issue. To this issue of Daughter's," a magazine where the vast majority of essays are written by people incarcerated, please click here.

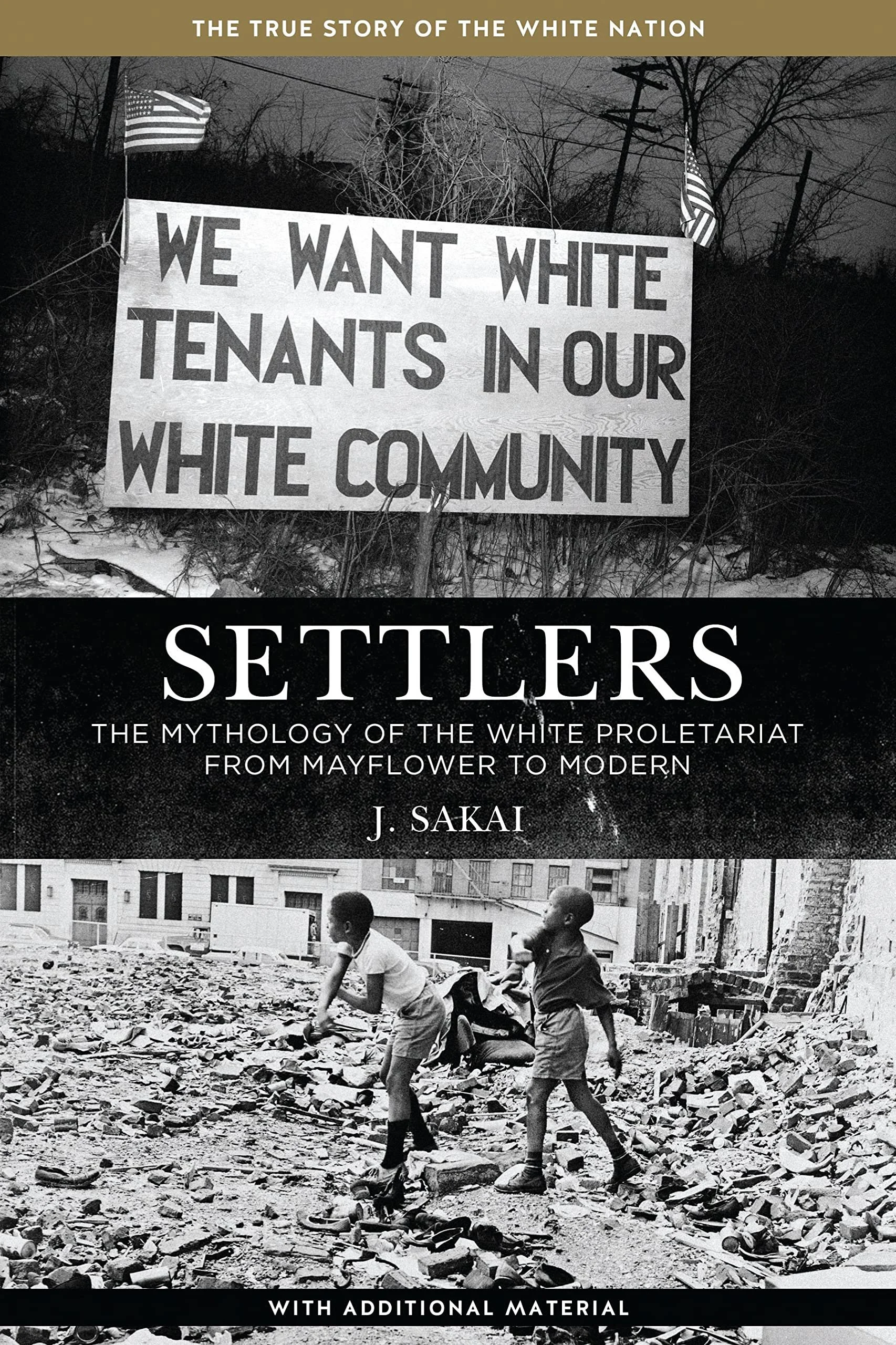

Cover of “Settlers: The Myth of the White Proletariat”